Learn to model 13 billion years of time with an inside look at a European Space Agency mission simulator.

Contents

🦀🦀🦀

Introduction

If you dream of the final frontier, but Montreal was a bit too far to travel, worry not – my RustConf 2024 talk is now available for all.

In just 25 minutes, you'll learn how to use Rust to model 13 billion years of time with femtosecond precision in seven astronomical time scales. No PhD required!

You'll also get an inside look at how these techniques are being actively applied in the space industry. This talk showcases my contributions to Lox, the Rust backend for Ephemerista, a next-generation space mission simulator funded by the European Space Agency (ESA).

Leave your questions – metaphysical or otherwise – in the Discussion, and I'll pick them up pronto. Keep in mind that I'm a Rust engineer, not a physicist, so I'll plead the Fifth Law of Thermodynamics if we stray too far from software engineering.

For those who prefer the silence of the void, here are the complete slides for the talk, and I've included my speaker notes below.

The talk

Speaker notes

Slide 1

Good morning! I’m Angus, and I am here to give you an inside look at Rust in the space industry. And, as a bonus, in just 25 minutes' time, you'll be able to model 13 billion years of time with femtosecond precision in seven astronomical time scales. No background in astrophysics required. It’s not rocket science.

We’re going to see how Rust is powering the next generation of space mission simulators. Because, to cross the final frontier, you need to know where it is, and how much fuel you’ll need to get there.

First, though, I’m going to release an elephant into the room by telling you that…

Slide 2

I’m a software engineer, not a doctor. I don’t have any formal education in astrophysics, and in my spare time, I teach Rust on my site, howtocodeit.com.

So if you’re wondering what credentials I have to be talking to you about space mission simulators, don’t worry – I had the same question.

When I was approached for this project, the lead told me they just needed skilled Rust engineers. But I thought, better safe than sorry, I will ask – "Are you sure I won’t need a background in astrodynamics?" And he said, “Yes”.

And that was a lie. So the last year has been quite uncomfortable for me. Not because astrodynamics is inherently, abnormally complex – but because historical astrodynamics code is often spectacular in its accidental complexity.

To show you how Rust is bringing balance to the Force, let’s establish some context.

Slide 3

I am a core team member for Ephemerista, a new, open-source space mission simulator.

It is wholly funded by the European Space Agency, and maintained by the Libre Space Foundation, a non-profit for the promotion of open source hardware and software in space.

When complete, it will include GUI mission planning and analysis tools, a Python API tailored to flight dynamics engineers and mission analysts, and pluggable integrations with existing tools, all backed by Lox, an ergonomic Rust astrodynamics library which is rapidly approaching v1.

Slide 4

An astrodynamics library has a lot of responsibilities.

- We’d like to know how to get from A to B, where A and B move in three dimensions and may be so massive that they alter the flow of time itself.

- Getting from A to B takes a certain amount of fuel, and to calculate that, we need a delta-v budget: the total change in velocity from the maneuvers we perform along the way.

- After launching our payload into space, we need to communicate with it. For that, we need to know the link budget of the mission.

- And of course, it would be nice to know how likely we are to crash our multi-million dollar spacecraft into into something else, particularly when it’s someone else’s multimillion-dollar spacecraft.

Spaceflight necessarily involves a lot of testing in prod, but without mission simulators, each launch would be equivalent to sticking your finger in the air and hoping for the best.

Here we see that, through simulation, Ferris has identified a critical vulnerability in plans for the galaxy’s most expensive orbital death machine, giving his employer the opportunity to correct the design before going to build.

Of course, we’ve all seen the documentary, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. We know how it ends, and this is because Ferris works for Boeing.

Slide 5

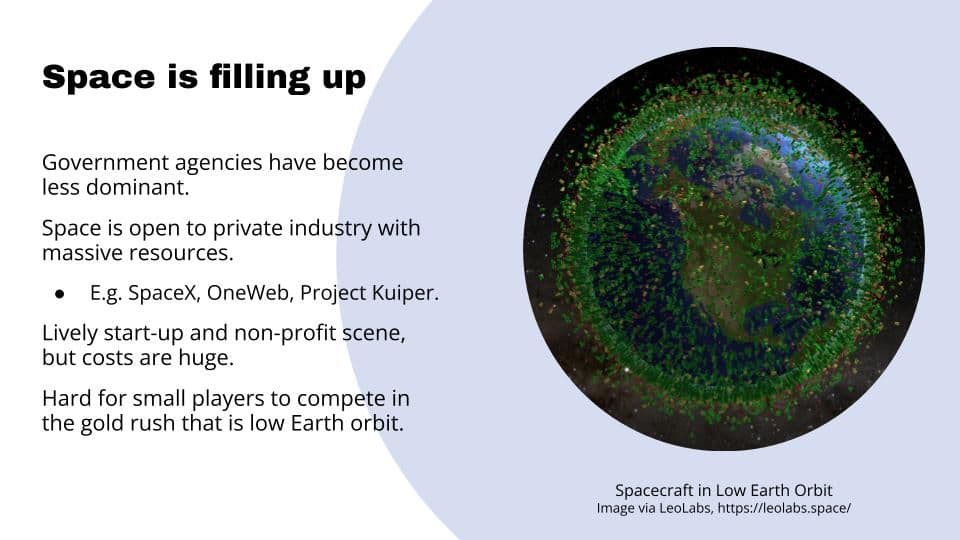

I keep saying “next-generation”, and not just for the Star Trek pun.

Space has changed dramatically in the last decade. Private enterprise has muscled into the ring, and the prize is real estate in low Earth orbit.

Ask any billionaire – super yachts? Very 2015. When Musk and Bezos get together to assert their masculinity, they flop it out on the table and compare the size… of their satellite constellations.

Networks of satellites flying in unison, communicating, providing global coverage at a fraction of the latencies achievable with satellites in geostationary orbits.

That’s a lot of satellites, and it’s getting crowded up there. The image here depicts the spacecraft, rocket bodies and large, named debris in low Earth orbit.

And, since the number of safe orbits is limited, we essentially have a gold rush in which it is extremely difficult for small players to compete.

If we value open access to space, high-quality, free, open-source software is a critical piece of that puzzle.

Slide 6

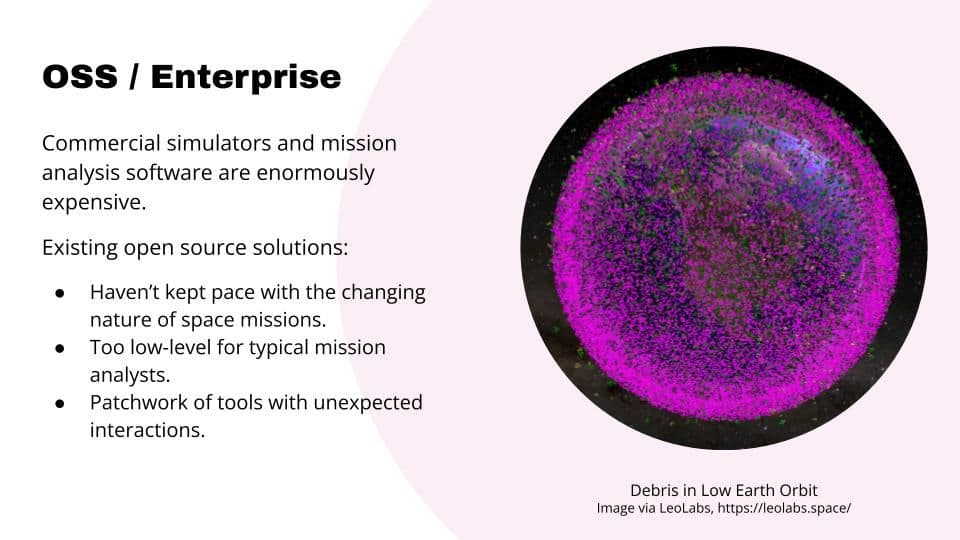

Commercial mission simulators are hugely expensive. They cost less than a rocket launch, but you’ll need a mortgage, not a credit card.

Meanwhile, existing open source solutions have tended not to keep pace with the changing nature of space missions.

For example, space junk is a massive problem. The image on the right is the debris that’s big enough to track but not worth naming. It’s doing 18,000 miles an hour. Cleaning that up is a whole new class of mission.

Another example – one of the sponsors of RustConf, K2 Space, is redesigning how we send mega-class satellites into space.

Support for missions like these has to be custom-built, and that carries substantial development costs.

And a typical mission analyst works at a higher level of abstraction than an astrodynamics library. This is the Python crowd. The people planning the missions are not the same people extending the simulator and start-ups must be able to afford both.

And even if they can afford both, combining old tools in new and exciting ways produces new and frustrating failure modes. In the 10th circle of hell, the guilty call Java astrodynamics routines from MATLAB and try debug the results.

Slide 7

So what makes Rust a better backend for a modern space mission simulator?

It’s fast, obviously. Python-based implementations like poliastro tend to struggle with complex trajectory calculations or propagating large numbers of orbits.

But using Rust doesn’t rule out Python for users who want a bit more control in a language they’re comfortable with. Lox uses PyO3 to expose Python bindings behind a feature flag.

Native compilation and portability are highly desirable. NASA’s free simulator, GMAT, doesn’t run on Apple Silicon. The last stable build dates to 2016. Orekit, the most successful open astrodynamics project to date, is written in Java, so like it or not, the JVM is coming along for the ride.

But most importantly, Rust is expressive. Rust is phenomenally good at communicating hardcore, domain knowledge to non-specialist developers, and that is the lifeblood of open-source projects.

To prove that to you, we’re going to do some domain modeling. Starting from a philosophical question, we’ll build up the real, prime time abstractions that underpin the lox-time crate.

So. A gentle warm-up question before we stare directly into the time vortex…

Slide 8

Slide 9

Well, I have a background in web development, so as far as I'm concerned, time began on January 1, 1970, and it's been going up in nanoseconds ever since.

If you take this view of the universe, time fits very nicely inside an i64. But there are two

opposing problems with this model in the context of a space mission simulator:

Slide 10

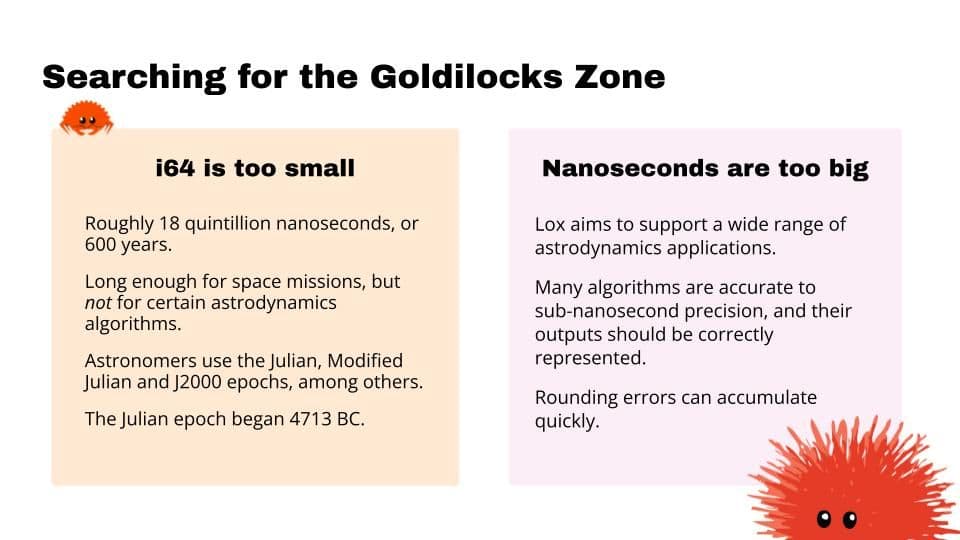

On one hand, an i64 is too small. It gives us roughly 18 quintillion nanoseconds to play with – about ±300 years.

While that might not be long enough to get those astronauts back from the International Space Station, it should be enough for most space missions.

It’s not enough for some space algorithms though. Astronomers don’t use the Unix epoch. Mostly they use J2000, which began midday, January 1st 2000, but the Julian epoch is also used, and that began 4713 BC. A qualified astrophysicist would tell you that's more than 300 years ago.

On the other hand, a nanosecond is a long time in space. Where we have algorithms that are accurate to fractions of nanoseconds, we’d like to be able to represent their output correctly.

And we should avoid snowballing rounding errors, since operations like orbit propagation are effectively pipelines of state calculations, in which each output is the input to the next iteration.

How do we improve on an i64 representation of time? Let’s try standing on the shoulders of giants and take inspiration from the time representation used by the International Astronomical Union’s “Standards of Fundamental Astronomy” – a collection of essential astronomy routines written in C and Fortran 77.

Fortran is like catnip to physicists. They can neither have nor want nice things. We going to look at the SOFA C representation, aaaaand…

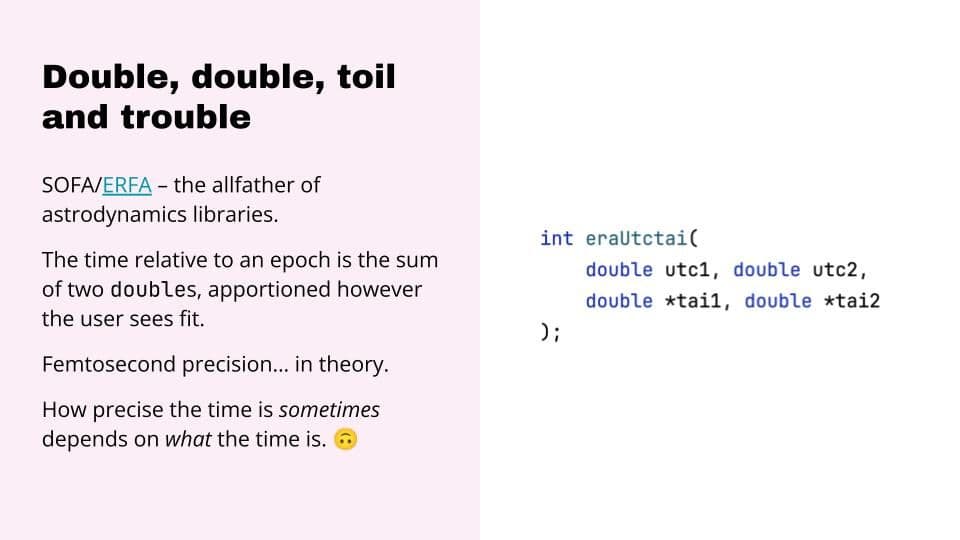

Slide 11

It’s… two doubles. Straight-up. Just two doubles. The time relative to some epoch, usually J2000, is represented as the sum of two 64-bit floating-point numbers.

How do you apportion the time between these two doubles, you ask? With great care!

Because this is C, where the behavior of your code depends on how well you read the instruction manual and how much you drank the night before.

The larger the integral part of each double, the fewer decimal places of precision your time supports. There is a correct way to apportion your time to reliably achieve femtosecond precision, but if you’re not up to date on your IEEE 754 floating-point arithmetic, how precise your time is will depend on what your time is.

Chef’s kiss.

There’s value here though. With a bit of type-driven Rust, we can codify the good ideas and prevent users from cutting themselves on the sharp edges.

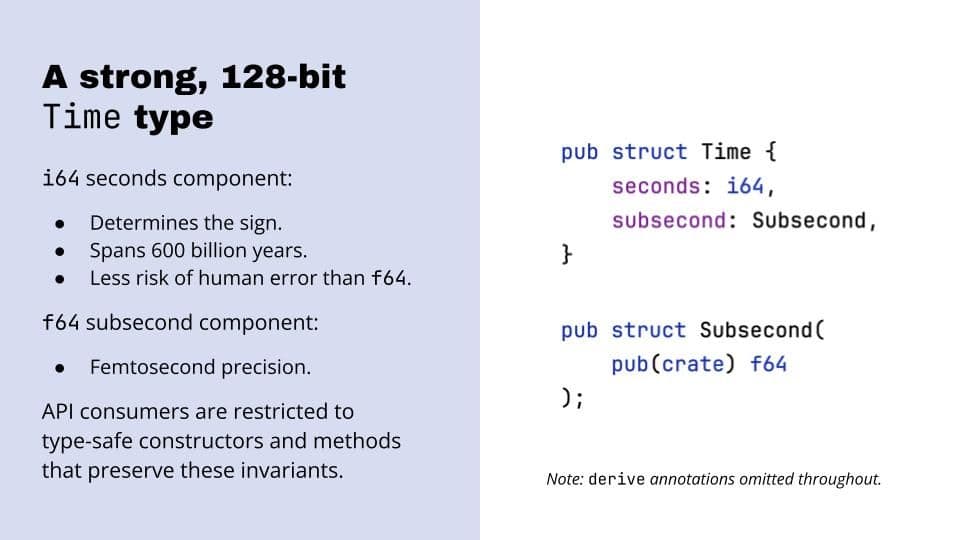

Slide 12

First, we take one of those doubles, and restrict it to an integral number of seconds relative to J2000. An i64 might not give us enough nanoseconds to play with, but it fits an order of magnitude more seconds than age of the known universe.

That leaves us to model the fraction of the current second. We initially tried using another i64 to count attoseconds since the previous second, but in practice, floating point arithmetic is so fundamental to physics that we’d have increased the complexity of the mathematical code while decreasing performance, and mission simulation isn’t concerned with anything happening at attosecond scale.

An f64 subsecond integrates nicely with established algorithms. But rather than use it raw, we define a Subsecond newtype to enforce the invariant that the f64 must be in the half-open range 0 to 1.

By restricting the f64 to the subnormal numbers, we guarantee that our time has always at least 15 decimal places of precision – femtoseconds.

Easy, right? A type-safe, user-proof, 128-bit Time representation.

Except… this doesn’t work.

Or rather, it’s not enough, because there is one thing to ruin it all–

Slide 13

UTC, or, as I’ve come to know it, the Devil’s Time Scale, cannot be unambiguously represented as a monotonic counter.

UTC is an unholy hybrid of International Atomic Time or TAI – an average of the world’s most expensive atomic clocks – and solar time, UT1, which is based on the Earth’s rotation. Which changes.

UTC is kept within ±0.9s of UT1 by the inclusion of leap seconds, which are decided about six months in advance by the International Earth Rotation and Systems Service. They have the best Christmas parties.

If I give you the time 536,500,836 seconds since J2000, are we at midnight on 1 January 2017, or 23:59:60 during the leap second of 31 December 2016?

And I say “inclusion” of leap seconds, not “addition” of leap seconds. Because leap seconds are allowed to be negative. They never have been, but they can be.

The speed of the Earth’s rotation changes over time. Since UTC was introduced in 1960, it has tended to slow, causing us to add leap seconds to stop UTC getting too far ahead of UT1. Since 2020, however, the Earth has been spinning faster, and if that trend continues, well, good luck being on call during a negative leap second.

Slide 14

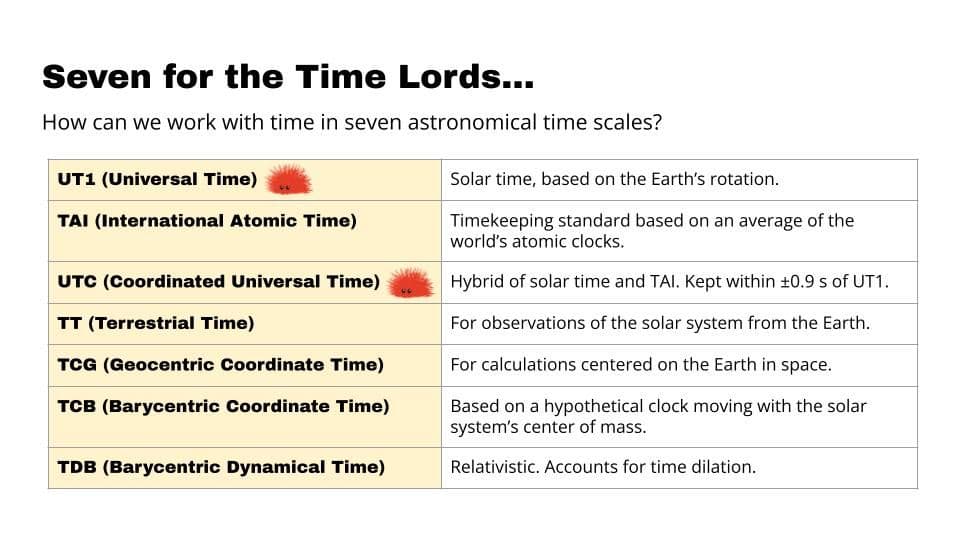

UTC is just the tip of the iceberg. Astronomers work with time in a minimum of seven time scales, from good old atomic time to TDB which is based on a clock that moves with the solar system’s center of mass and accounts for time dilation.

On this slide, you’ll see that Corro the Unsafe Rusturchin is marking the two extra fun timescales that can’t be determined without external data.

Lox has to model all of these and transform between them in an ergonomic, intuitive way. Let’s start with the representation of the time scale itself.

Slide 15

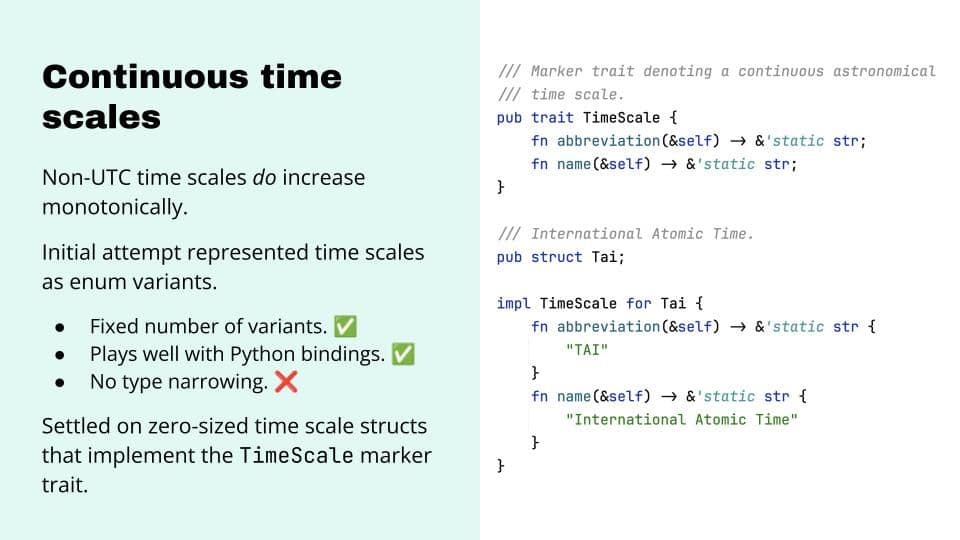

Luckily, every timescale that isn’t UTC is guaranteed to increase monotonically. Our base time representation with an i64 second and an f64 subsecond is sound – we just need to pair this data with some indicator of its timescale.

We initially tried representing time scales as enum variants. At first glance, an enum seems like a good fit, because the number of variants is fixed, and it wouldn’t require any special treatment when mapping to Python.

But we can’t specify bounds on enums like we do with traits. We can’t define a function that accepts only the TAI variant of a TimeScale enum, for example, and different algorithms have inputs and outputs in different timescales.

Instead, we defined a TimeScale marker trait and implemented it for a dedicated, zero-sized struct for each time scale.

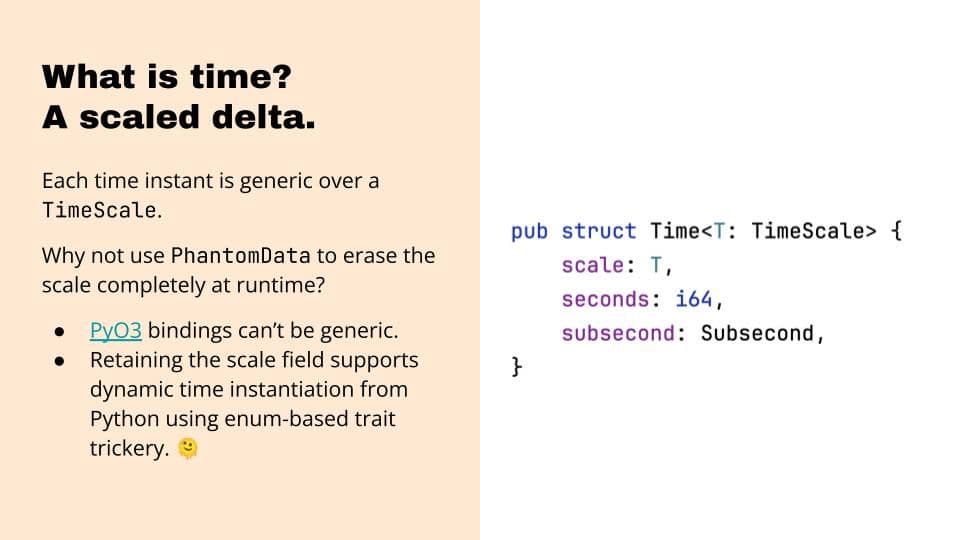

Slide 16

With TimeScale as our trait bound, we can implement a generic time type that combines a delta since an epoch with a scale – and since each TimeScale is zero-sized, it takes no more space than the raw timestamp.

Which might lead you to ask if the scale field couldn’t just be PhantomData? Maybe Einstein was wrong? What if time isn’t physical reality, but a figment of the compiler’s imagination?

Unfortunately not. Nature works in mysterious ways, and since Python is a dynamic language, Python bindings cannot be generic. By retaining the scale field, we preserve the ability to instantiate Times dynamically using some enum-based smoke and mirrors that, unfortunately, I don’t have time to go into.

If you don’t need Python, rest easy in the knowledge that this field weighs nothing.

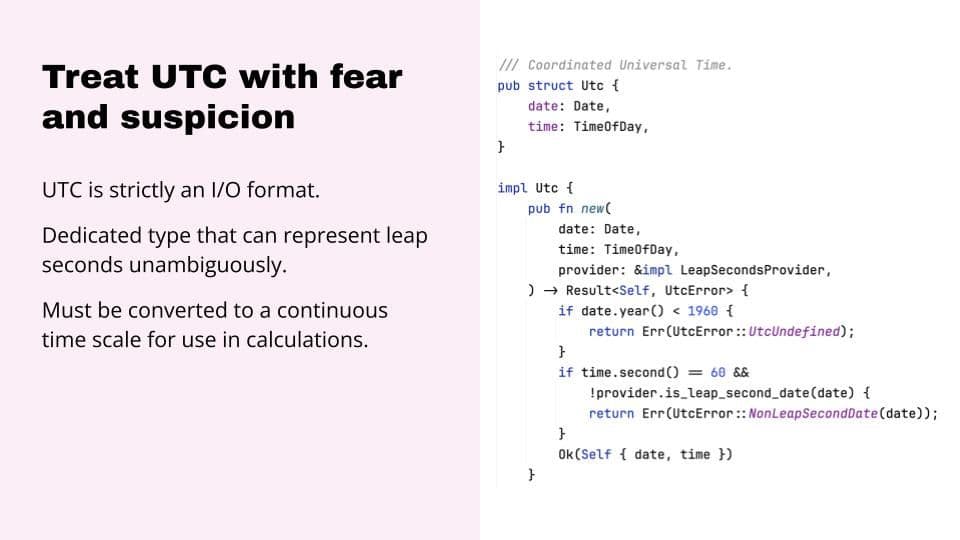

Slide 17

Back in the Land of Shadows, we made the decision early that, although we can’t cast UTC into the fire, we can contain it.

UTC gets a dedicated year, month, day, hour, minute, second, subsecond type which exists at the boundaries of the lox-time crate. It is treated strictly as a human-readable, I/O time format which must be converted to a continuous time scale for use in calculations.

Flight dynamics engineers expect to input times in a format they understand. This is a reasonable expectation of an unreasonable time scale, and we do significant legwork to hide that complexity from the user. The Utc type is leap-second aware, and ensures that each transformation to other scales is unambiguous.

We achieve that through the LeapSecondsProvider trait. Lox provides a default implementation, which I wrote – and experience violent flashbacks about to this very day.

We don’t have time to get into the implementation, but do feel free to ask me your leap second questions in the Discord chat for this talk.

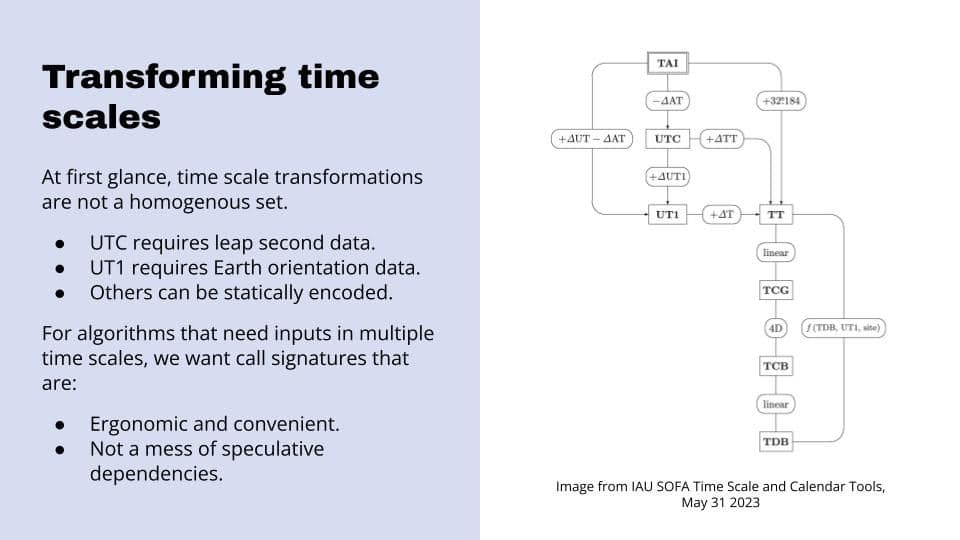

Slide 18

How do we specify time scale transformations?

The graph on the right shows how each time scale maps to the others, and some of these appear to have very little in common.

TAI to TT is my absolute favorite. Just add 32.184 seconds. This is kind of simplicity I live for. This is the stuff of dreams.

TT to TCG is a linear transformation, but the next edge from TCG to TDB is a four-dimensional transformation. More complex, certainly, but this data can be specified statically and compiled into your binary.

However, as we already know, conversions involving UTC need historical and upcoming leap second data.

And UT1, being solar time, isn’t technically a time at all, but the orientation of the Earth with regard to the Sun. You might be surprised to learn that we are actually unable to model the rotation of the Earth with enough accuracy to predict how UT1, UTC and TAI will differ more than about a year in advance. This is why we only get six months’ heads-up on new leap seconds.

That means we need a current source of Earth Orientation Parameters based on observed data, and library users should have the option to provide their own data sources.

Given our stated goal of an ergonomic and intuitive API for astronomical time – this appears to suck. How can we provide a high-level interface that is convenient to call with whatever timestamp the user has to hand, without creating a mess of speculative dependencies for unrelated transformations?

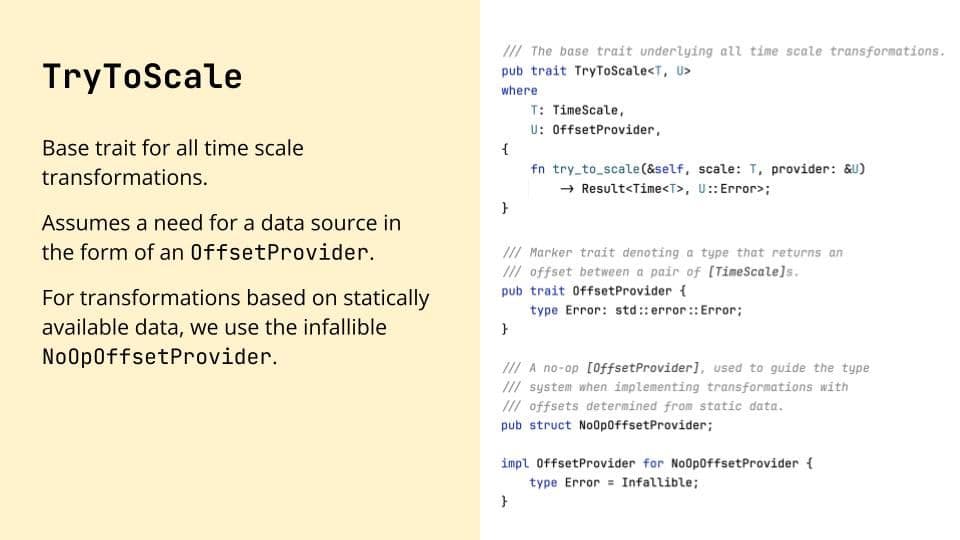

Slide 19

If we squint, however, we can just about make out a homogenous set of time scale transformations. And with Rust, we can fluently articulate this relationship in code.

TryToScale is the base trait underlying all of Lox’s time scale transformations. It is supremely pessimistic. It assumes that every time scale pair requires an external data source in the form of an OffsetProvider implementation, and that that OffsetProvider is fallible.

TryToScale doesn’t care that TAI to TT is simple addition. It is a hammer, and every transformation is a nail.

We know better, of course. Most transformations – constant, linear, or four dimensional – are infallible, and the first step on our journey from blunt instrument to keen edge is to implement OffsetProvider for NoOpOffsetProvider, a zero-sized struct that does nothing, without fail.

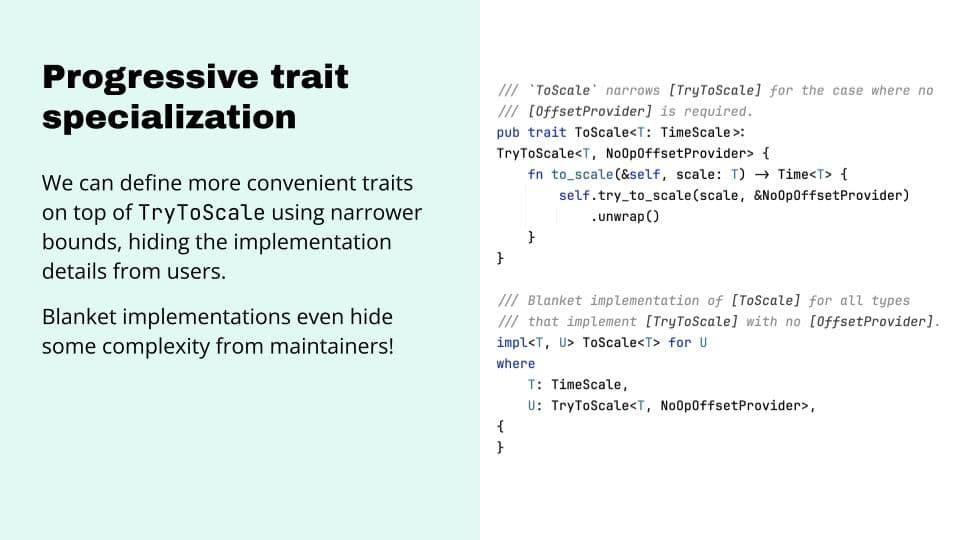

Slide 20

This starts a process of progressive trait specialization, where each tightening of the trait bounds exposes a more convenient but more situational subset of time scale transformations.

We define ToScale, bounded by an infallible TryToScale based on NoOpOffsetProvider. We don’t want to force callers to handle failures that cannot happen.

Even better, we can blanket implement ToScale for any type that implements an infallible TryToScale, saving the maintainers the headache of doing it manually. Thank you, Rust.

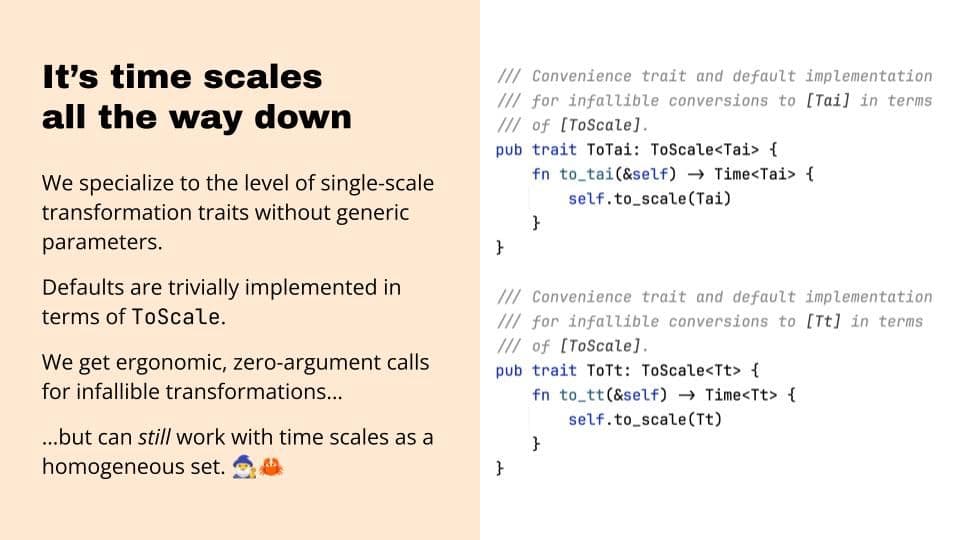

Slide 21

This process continues to the level of single-scale transformations. Traits ToTai, ToTt, and so on, specify zero-argument, infallible methods with default implementations for all pairs of simple transformations.

This is amazingly convenient, and Rust gives us that convenience readably, statically and without sacrificing the ability to work with time as a homogenous set.

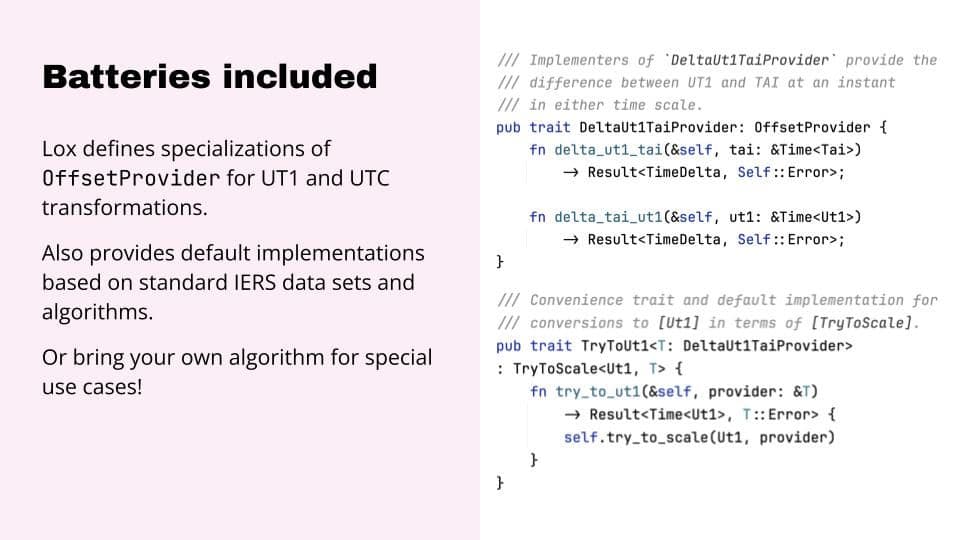

Slide 22

What about fallible transformations?

You’ve already seen LeapSecondsProvider in our discussion of UTC, and LeapSecondsProvider is in fact a specialization of OffsetProvider.

We do the same for the UT1-TAI pairing, which depends on data derived from observed Earth Orientation Parameters. DeltaUt1TaiProvider is a specialization of OffsetProvider, and TryToUt1 is a specialization of TryToScale over a DeltaUt1TaiProvider.

There are no ToUt1 or ToUtc traits, because they are fundamentally fallible operations.

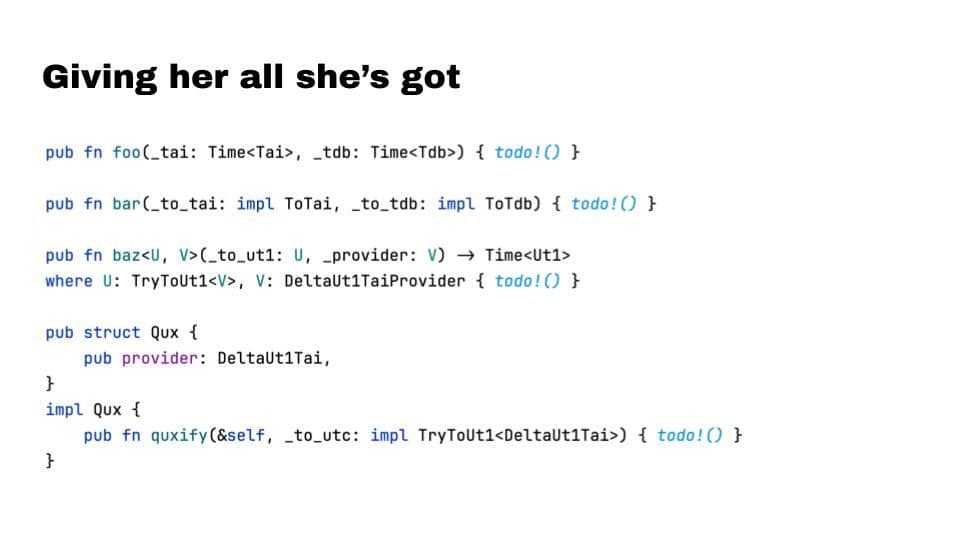

Slide 23

Putting it all together, we have a collection of traits that allows Lox and third-party users of the lox-time crate extraordinary flexibility to design types and call signatures based not just on the concrete timescales that a particular algorithm requires, but on the graph of time scale transformations.

Rather than “give me TAI” we can say “give me any, infallible path to TAI”. You can say “give me a path to UT1 and the observed data to traverse it” OR you can say “I have observed data, give me the path that consumes it”.

And that is how you model all of time in Rust.

Slide 24

Thank you so much for listening, you can find Lox on GitHub at the link in this presentation. For the YouTube crowd I will bat my eyelids at the organizers and ask them to put a link in the description.

You can find more of my work at howtocodeit.com or reach out to me directly at angus@howtocodeit.com.

I will be taking questions after the talk. Remember, I am not an astrophysicist – if you ask questions me questions too far from Rust, I reserve the right to not publicly embarrass myself.